In 1971, the brothers McKenna, one of whom would go on to become the archduke of the psychedelic counterculture, made their way to La Chorrera Colombia for an experiment with hallucinogens that drove them both mad.

Terrence and Dennis were following the trail of a rare plant brew which they’d read a paper in the Harvard Botanical Musuem’s journal. The paper described how the Witoto tribe turn the Virola tree’s sap into a DMT-containing blend called oo-koo-hé. The boys, in their early twenties, travelled four days through the jungle to try it.

What became known to them as The Experiment at La Chorrera sounds to me about as far as you can go into the weird realms of high-dose DMT experiences.

It all began after a hefty dose of Psilocybe cubensis they’d found on the way. Dennis began to hear a buzzing static sound in his head which he couldn’t figure out how to interpret. As the rain outside of their cabin ceased, they all heard the faint static sound of an FM radio being carried by someone walking nearby. This sound and its symmetry with the one in his head flipped a switch inside Dennis. He started to shout absurdities and the experiment began.

After this intense experience, Dennis started to develop a bizarre and mostly incomprehensible theory that would guide the crew into their main journey with DMT. A taste:

“When the ESR tone of the psilocybin is heard via tryptamine antenna, it will strike a harmonic tone in the harmine complexes being metabolized within the system, causing its ESR to begin to resonate at a higher level. According to the principles of tonal physics, this will automatically cancel out the original tone, i.e., the psilocybin ESR, and cause the molecule to cease to vibrate; however, the ESR tone that sustains the molecular coherency is carried for a microsecond on the overtonal ESR of the harmine complex.”

The boys weren’t just looking for a weird time. Their diaries and memoirs document some grand aims for the trip: they were using DMT to change the world. They believed that they might be able to construct a new sort of physical object, a spinning hologramatic disc, that would act as an entirely unpredictable destablising force on consensus reality around the world. Instead, Dennis entered psychosis for weeks.

When I first heard Erik Davis (who has an excellent substack here) tell this story in High Weirdness I was washing up in my girlfriend's kitchen and pretending to be listening to something less strange. I decided to slot it into the ‘weird/bizarre’ category of my brain and leave it at that. But over a year since then, I’ve been chucking a few other things in that jar and it’s all fermenting into something else.

Davis is a much better historian of the psychedelic counterculture than I ever could be because he has the capacity to take the experience of trips like this seriously in a way that I struggle to (spinning discs to change the world, really?). In his retelling of The Experiment he is able to extract kernels of insight that put paid to the simplistic assumption that the druggie, esoteric and weird parts of the 60s and 70s were distractions from real political radicalism.

One such kernel is the weird and illuminating role of resonance.

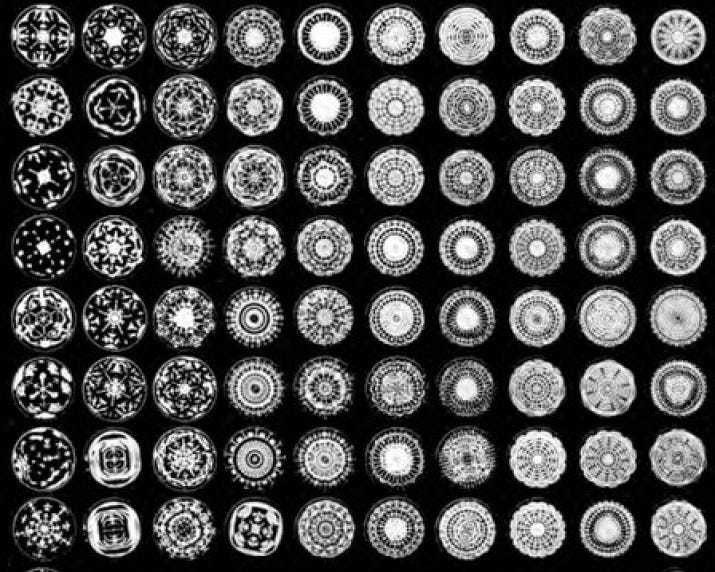

As Davis handles it, resonance traverses (or resonates across) the physical sciences, literary metaphor and spiritual exploration. The most generative aspect of it is the phenomena of sympathetic resonance - the thing that happens when a guitar string vibrates it causes its neighbouring strings to vibrate at the same frequency, or when an opera singer finds the exact pitch they will be able to smash a wine glass. But these are only the particularly visible examples of what is a foundational feature of the universe.

Just look at the existence of mechanical resonance, Orbital resonance, acoustic resonance, electromagnetic resonance, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), electron spin resonance (ESR) and resonance of quantum wave functions, for a snippet of how far this phenomenon repeats.

The McKennas -Dennis in particular- started to focus on resonance as a powerful amplifying force for their experiment early on. The day after he first heard the buzz inside him, Dennis began to experiment with humming in a way that matched the sound, constructing, as Davis puts it, “a sympathetic vibration out of his voice”. In doing so Dennis experienced an intense amplification of the power of his voice and the internal humming, transforming both into a much more powerful force than just the sum of their parts. Pretty soon it all got too much, and his brother had to step in to calm him down.

While they were playing with the physical properties of sonic resonance, there was another kind of resonance emerging. The boys found themselves in an intoxicating state of conversational flow: wordplay, half-remembered histories, connections between ideas, symmetries, synchronicities, and jokes all seemed to be propagating one another. They had, in this more interpersonal and social way, entered a much more resonant space.

This other kind of resonance brings us closer to the radical content of the McKennas’s excursion into delirium. Kae Tempest, the poet and musician, gets to it in their work On Connection. Kae’s meditations on creativity, connection and art derive from their understanding of resonance: “All objects have a frequency at which they resonate. Including you.”.

The feeling Kae’s trying to pin down in the whole essay is one we can all recognise about the experience of resonance: it’s when the world makes more sense, we feel connected to it and our interactions with it seem to mean something.

It’s one of those nights sitting around with some friends, people who’ve known each other for years, when suddenly a topic comes up that you’ve never discussed before - a TV show, an experience of abuse, a favourite poem, a secret dream, whatever - and everyone shares something totally new. People sit up straighter, ask more careful questions, stare off for a moment, and are astonished. This is a resonant space. The world shrinks, expands, blurs and clarifies: consciousness gets raised. Kae Tempest calls it “landing in the present tense”, “a feeling of being absolutely located”.

“...anyone who’s ever meditated, prayed, studied the stars, cooked an important meal for people they love, thrown a punch, received one, built something with their hands, learned a skill because they had no choice, been in service to others, volunteered their time, found themselves at the edge of their sanity or at the edge of their experience, accepted a difficult truth, put themselves second, genuinely gone out of their way for somebody else, has felt it” (italics mine).

To say something ‘resonates’ is a bit of a new-age cliche. My working-class friend used it as the decisive tell when describing the insufferability of a group of middle-class meditators they were working with. But at the same time resonance is having its own revival as an animating idea of certain pockets of the anticapitalist movement.

I first spotted it in The Future Is Degrowth, currently the handbook on the degrowth movement. Degrowth, as the authors put it, is not only about opposing a society built on the endless accumulation of capital but also articulates a vision of a good life for all. They invoke buen vivir, conviviality, time prosperity and resonance as the constituent elements of this vision. “Resonance”, they say “is a counter-concept to acceleration and alienation and offers a yard-stick for meaningful and good self-world relationships – instead of constantly expanding individual world reach by increasing the number of accessible goods, experiences, and encounters, the focus is on establishing fewer, but stable, axes of resonance.”

Following the footnote trail from here takes us to the work of a German sociologist called Hartmut Rosa. Rosa has spent 10 years thinking through the way that resonance, as a central idea, can help reconstruct a sociology that both remains receptive to the world, allows for critical evaluation and suggests an alternative.

The social sciences (and the political movements which adopt their ideas) have for too long been using the framework of capitalism to evaluate what constitutes a good or successful life. Wealth, educational attainment and status, for example, are taken as given for what people need, and advocates for social justice, according to Rosa, find themselves unable to ask for anything other than a relatively superficial redistribution.

Resonance offers a way out. Humans are connected to the world via a “vibrating wire”, the quality of our lives can be judged based on this wire's ability to resonate, that is respond, adapt and transform without coopting the world. When this wire goes mute, as it is wont to do in these later stages of capitalism, we find ourselves alienated, in a “relation of relationlessness”, and at its worst, depressed.

The central paradox of modern culture is its urge to commodify and capture resonant experiences, while in doing so it forecloses any possibility of it. Similar to the Buddhist concept of ‘grasping’, our continual reaching for attachments pushes us further away from reality as it is.

Control dampens the wire. It keeps us from the experiences, that William James quoted by Rosa describes as “moments when the universal life seems to wrap us round with friendliness. In youth and health, in summer, in the woods or on the mountains, there come days when the weather seems all whispering with peace, hours when the goodness and beauty of existence enfold us like a dry warm climate, or chime through us as if our inner ears were subtly ringing with the world’s security”.

Resonance, according to Rosa, is essentially anticapitalist because it cannot be commodified. It is anathama to the way our economic system continuously expands and accelerates. This is probably also related Davis’s argument that resonance has an antimodern (antirationalist) character, because of the way it blurs the boundaries between subject and object.

Rosa has big dreams for this idea. Critical theory has been stuck in a state of pessimism and melancholy since it was first fleshed out by the Frankfurt School. While relativism in the social sciences has shied away from advocating for any particular alternative. There has been a hole where positive vision of the world we want, at least in academia, should be. Resonance is his way of fixing this.

It’s funny that 50 years ago just as the countercultural wave was reaching its peak only to recede into the decades of reaction we have endured since, resonance was being explored for its radical potential.

The McKennas are somewhere in between the caricature of the apolitical hippies and the political discipline we now know is key to lasting social change. Terrence was heavily involved in the late 60s campus politics and found himself part of many street fights with police at the University of California. And yet he said to his friend a few days before visiting La Chorrera that “The political revolution has become too murky a thing to put one's hope in. So far, the most interesting unlikelihood in our lives is DMT, right?”

Terrence’s politics shrunk in the years that followed. His public advocacy became limited to large numbers of people taking large amounts of LSD. As Davis points out, these drugs do not have a determinate agency all by themselves. They will definitely do something, but what that something is depends on how it slots into an existing field of ideas, objects and emergence.

Psychedelics are not like a sedative or an anti-inflammatory pill. Their effects are highly unpredictable. This leaves plenty of room for the so-called ‘psychedelic renaissance’ happening in this third decade of the 21st century to share the qualities of the first wave and take it somewhere new, politically radical and socially transformative.

Great to read these postulates but here they all appear to be proposed by men?