Land, visions, fantasies and farmers

how to fight the regen ag delusion with agroecological dreams

Last year, at a friend’s funeral in our village, my Mum met a farmer who wanted to meet me. He has a company which farms 22,000 hectares of land, employs 900 people and sells over £500 million worth of crops a year. I have a criminal record, a negative bank balance and a distrust of large landowners. I cycled over a few days later.

We had a tea in his eco-glassy-woody office, and then he took me for a drive in his electric Jaguar. In the fields, he pointed out plastic reduction efforts, talked vaguely about protecting peat and described how excited they were about ‘regenerative agriculture’.

Our environmental crises -the reason he wanted to chat with someone who’d been part of XR- were not lost on him. He described a deep sense of duty to respond by stewarding his land well, and regenerative agriculture was offering him a way to do that.

I don’t know why he wanted to let me know. I mumbled some stuff about the end of the world and left.

On the face of it, we love regen ag. It’s an umbrella term for an alternative to industrial farming. It means, no more monocultures (endless fields with all one crop), no more pesticides (ecosystem-destroying chemicals) and no more artificial fertilisers (soil and river pollutants). It means protecting soil by cover cropping, not tilling and growing green manures. It also means creating habitat for pollinating insects, birds and other mammals that might support the food web. The promise of regen ag is that we can grow more food, at higher quality, and heal exploited landscapes.

The problem - as I couldn’t help notice cycling home through vast exposed fields - is that enormous farm holdings, organised centrally and hierarchically to maximise revenue, can’t do this. Intricate crop polycultures, careful protection of soil life, regular hand-weeding and close attention to the predator-pest ecosystem, need lots of people with intimate, non-commodified relationships to the land.

I don’t know if this farmer got much from our interaction, but it opened my eyes to the way regen ag is facilitating a fantasy amongst British farmers. It is built on lifting the ‘good bits’ from successful small-scale agroecological (and often indigenous) farms while ignoring realities inconvenient to large landowners. Regen ag is to farming what renewables are to Shell: at worst a ploy, at best a barbiturate.

The delusion depends on removing the question of people from farming entirely. A peek at the Groundswell Festival topics (the Glastonbury of regen ag) shows a focus on yields, mechanical interventions and cultivation techniques. The question of people and how they relate to land is barely an afterthought.

There are historical reasons for this. Because England was arguably the first country to be colonised, our land ownership is extraordinarily unequal. 1% of people own 50% of the land. Since the Norman invasion and in particular, during the enclosures between 1600 and 1800, almost everyone has been permanently excluded from the land that once sustained them. It was a foundational moment in the history of capitalism: the thousands of people needed to work in the new industrial economy would only do so because they no longer had any other means of survival.

The ideology that enabled such large-scale dispossession was the story of underused land. It was a terra nullis, wasting away, in need of modernising. For instance, in the Fens, where I and this farmer are from, the indigenous Fennish were painted as backwards, uncivilised barbarians who, despite having intricate systems of common usage, an extraordinary variety of foraging and cultivating techniques and centuries of coexistence with wildlife, didn’t deserve the land they had. This was, of course, the first draft of a story retold across the British Empire in the following years.

Regen ag is a product of this history. It’s why when large-scale farming conservation projects do think about how people will relate to the project, their main concern is to keep them out. We’re left with well-intentioned but alienating rewilding projects like the Knepp, Mapperton or Broughton Estates -vast private landholdings, acquired predominantly with the profits of slavery and colonialism- amounting to what critics call a new land grab.

We need a countervision, and there is one. It comes from the global south. It is rooted in indigenous cosmologies. It doesn’t separate food production, thriving ecosystems and human social relationships. And hundreds, if not thousands, of small-scale growers, with much more radical intentions, are practicing it across the country. It’s called agroecology, and it’s thriving on the margins.

But, with Nestlé and McDonalds piling resources into regen ag research institutes, agroecology needs to be fought for.

To work out how, Emma Cardwell, a radical professor at Lancaster Uni, says we should look to Latin America. Across the continent, the movement for sustainable agriculture has the question of people front and centre. And it has everything to do with how progressive social movements have taken food production seriously.

The Zapatistas are the most obvious example. Since bursting onto the scene in 1994, their icon of the peasant farmer in a ski mask has replaced Che Guevara in dorms worldwide. Just at the moment when every other alternative to capitalism seemed to be in retreat, they have become a beacon of the global anticapitalist movement. And, as is the case in Cuba, which only survived the fall of the USSR because of its strong agroecological infrastructure, the Zapatista's capacity to effectively succeed from the Mexican state has been sustained by its capacity to grow food in regenerative, low-input ways.

Their farming methods have lineages thousands of years old. At the heart of all seven indigenous communities that make up the movement, is corn, a sacred plant. To the Mayans, whose calendar is based on the life cycle of corn, the plant is akin to an ancestor. The Zapatista’s struggle for autonomy from US corn markets and the imposition of ‘Green Revolution’ industrial farming methods is based on reviving this ancient relationship.

In practice, this revolves around something called the milpa system. Milpa is a cultivation method that, like the three sisters in North American indigenous culture, includes corn, squash and beans, but combined with chillies, mushrooms and fruits. It is a complex polyculture impossible to reproduce for commodification. It depends on intimacy.

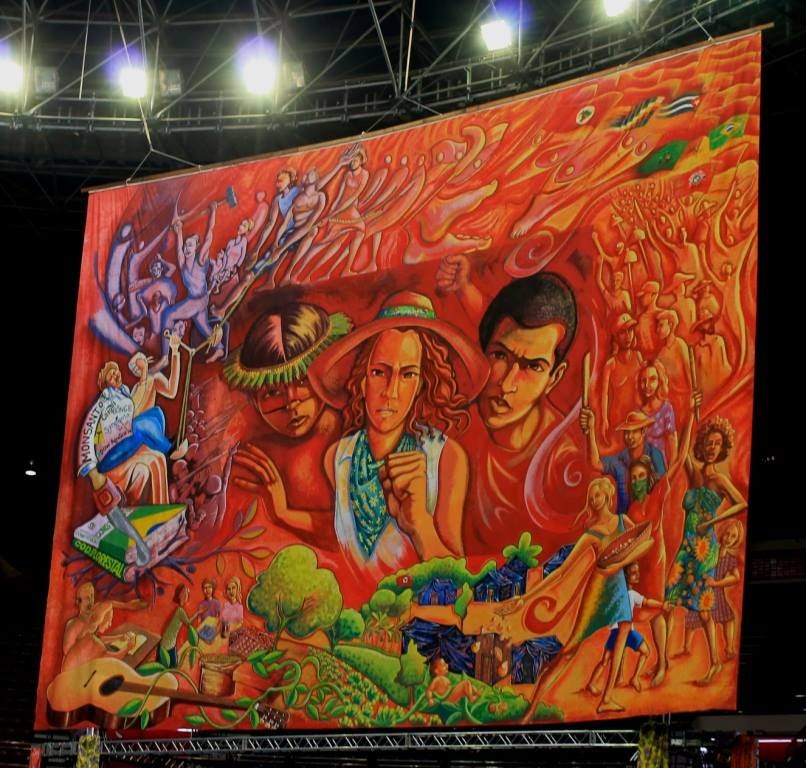

While there is a lot to learn from the Zapatistas, there is another movement that we might draw more direct lessons from, but, perhaps because of their explicit commitment to Marxism, it is far less well known. The Brazilian Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra or Landless Workers’ Movement (MST) has grown to a membership of over two million people in the last 30 years. 460,000 MST families have reclaimed abandoned and mismanaged land, built over 400 agroecological cooperative enterprises and helped defeat Bolsanaro in the most recent election. Their strength has international significance. In the 90s they helped found La Via Campesina which has become a powerful global organisation representing the millions of small-scale farmers who produce 70% of the world’s food.

The MST has a long history in the struggle for justice in Brazil. The constitution won by the movement for democracy in 1985 contains a clause that legally justifies the MST’s occupations. Land that is unused, exploited or not serving the community can be expropriated with fair compensation, it says. By occupying land and cultivating it carefully, the movement is keeping the government accountable to this constitutional right. There are two core aspects of the movement that explain its success and that other agroecological movements could learn from.

As is true of the birth of many social movements in the 20th century, the MST involved a committed group of urban intellectuals moving out of the city to build a mass organisation of peasants. What has made the MST successful (compared to say the Naxalites in Southern India) is their openness to the existing radicalism of the indigenous cultures they found there. Inspired by Antonio Gramsci’s idea of the ‘organic intellectual’ as well as in Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, these militants learnt from and were led by the peasant farmers they aimed to organise.

This is one of the reasons the movement today is grounded in ecological cosmologies and earth-based spiritualities. Most observers seem to agree the longevity of the radical politics grows out of this foundation. In the MST militant José Maria Tardin’s words “the multiplicity of cultural ethnic foundations expressed in the cosmovisions and praxis of the continent’s ancestral peoples (...) and enslaved Afro-descendants” shape a movement that “is radically anti-capitalist and anti-patriarchal, and is of socialist orientation”.

From here, agroecology becomes much more than a simple alternative to the failure of industrial agriculture. It is more like a lightning rod for a vast, scattered landscape of indigenous, black and radical traditions, or a frame, maybe, to weave a pluriverse of knowledge systems, ‘a world’, as the Zapatistas say, ‘in which many worlds fit’.

In an extremely unusual outcome for a movement against the state, the MST also run hundreds of state-funded rural schools and convene several university degrees. Rebecca Tarlau, an American academic who’s spent years in them, describes the schools as places where:

Activists teach students the importance of farming as well as studying and encourage cooperative forms of work and holistic learning. They envision schools as democratic spaces, where parents, teachers and students decide together how education should function. They want teachers to help students analyze contemporary and historical inequities in their communities, so the students can help transform these conditions. By applying these curricular and organizational principles, MST activists are trying to create an educational system that encourages young Brazilians to stay in the countryside and become farmer-intellectuals.

Imagine if all of our agriculture colleges were populated by these kinds of dedicated political ecologists. What if Schumacher College was the norm? And imagine if our schools, not only facilitated children learning about the natural world (a low bar that isn’t even being reached), but encouraged a critical understanding of the history of our relationship to land. What kind of movement could we build then?

When I started writing this, I thought it was going to be a simple story: Regen ag in England just needs politicising. It needs to break out of its narrow fixation on technical adjustments to a broken system and ask bigger questions about social relationships. Easy. But Abya Yala’s roaring movements suggest that a capacious, resilient politics needs to be rooted in rich, earthy cosmovisions. Which makes you wonder, what shreds of a land-based culture remain here? What does that have to do with the boys on the council estate in Colchester? Is re-peasantisation even thinkable in such a completely commodified, post-industrial landscape?

At the very least, our comrades across the water remind us that the way food is grown is tied to political aspirations. The two weave, interact and co-propel one another. It is a subtle and expansive bond. It is the way that the land calls to be loved, love being a radical practice of care, and commodification precluding care; it is how diversity is inherent to resilient, thriving ecosystems, agribusiness is incapable of maintaining diversity, and so diversity depends on land redistribution; it is people fundamentally connected to places, where we gather our ability to survive, and capitalism seeking to eradicate that ability.

In the words of Walter Pengue, an agroecologist from Argentina, it ‘implies a revolutionary social process, which has fully understood that the human being is nothing without the land he treads on.’

The farmer I spoke to hosts community days once a year. I’d never heard of them, which didn’t surprise him. No one comes, he sighed. ‘How are we supposed to get people interested in where their food comes from if no one cares?’ I nodded sagely.

What to say?

The earth is an infinitely complex place. If we’re going to cultivate it, it’ll require deep forms of care. Land stewardship isn’t a profession that can be nobly outsourced to a few. If these farmers really want to be good stewards they’ll need to be part of reviving a much older widespread form of intimacy with life.

If I were them I’d start reaching out to the hundreds of young aspiring agroecological farmers in the UK and offering them low/no rent, long-term leases and distribution support. I would experiment with giving access to parcels of land to committed community groups who would steward them. If they want a genuinely regenerative agriculture they need to think through how their infrastructure could be transitioned to support the distribution efforts of a cooperative federation of small, diversified, organic farmers. It’s not unheard of for farmers to do this. (Riverford Organic’s owner recently converted his business into full employee ownership.) But there’s a fair bit at stake to count on it. They’ll probably need a nudge.

Very insightful and inspiring stories. I hope you get/got the chance to discuss these with that farmer!