“The forest garden is (...) a way of life” (Robert Hart). It is a way “to recreate the Garden of Eden” (Jacke and Toensmeier). “Discovering forest gardening divides my life into before and after, just like having children or finding your life partner.” (Anni Kelsey). Which is to say, for some reason, forest gardening is more than just a set of gardening techniques.

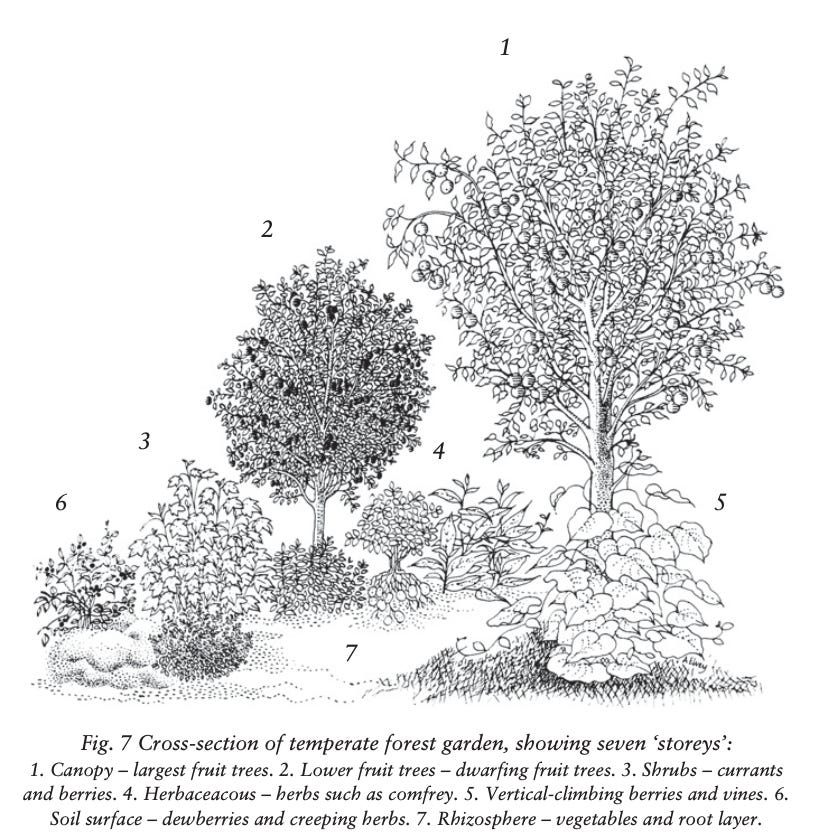

If you don’t know, forest gardening is where perennial crops (plants that live longer than a year) are densely combined along different vertical layers: a ‘multilayered polyculture’. Where classical horticulture keeps the garden in a constant state of infancy (annual plants are the first in the process of land becoming forest), forest gardening allows the land to progress into more and more complex ecosystem of fungi, roots, flowers, shrubs, bushes and trees. The result is somewhere between an orchard and a forest. But why does it mean so much more than this to so many people?

Forest gardens do feel different. They’re intimidating in some ways. Chaotic. Unusual. Busy. But with a guide or the right knowledge, they become wondrous. In a forest garden, everything is doing something for everything else. Trees feed soil feed shrubs feed insects feed birds feed fungi and so on. The variety of offerings for us -staples, sweet treats, spices, teas, medicines, and crafting materials- is overwhelming. This description of a forest garden in England captures the feeling: “It shimmered with a special sort of energy. It felt safe, enclosing, and enfolding. It was wild, in a mild-mannered sort of way. It felt like a forest, but it also felt like a garden. This combination truly holds a special magic.”

The propaganda potential for these gardens is enormous: yields are higher, biodiversity is higher, climate resilience is higher, and soil is built rather than destroyed; meanwhile, the nutrient inputs required are lower, and far less energy is needed to maintain it. For many advocates though, these technical successes aren’t as important as forest gardening's promise of a different way of being in the world.

Forest gardens push human culture (from the Latin colere - to cultivate) towards something wilder, and reward you for it. The idea is satisfying to those of us with the Christian cosmology that equates redemption with a return to the garden of Eden and a pure, sin-free life. And it satisfies whatever remnant of pre-Christian cosmology we still have that says modern civilisation is doomed if it doesn’t recognise and honour the spirits of the land.

Forest gardening promises communion and a return to our proper role in the web of life. Anni Kelsey, whose 2020 book The Garden of Equal Delights is one of the freshest reflections on the meaning of all this, says forest gardening “is a process of unsettlement. You are being uprooted from your previously assured place at the top of the evolutionary tree and being replanted in a much smaller niche, lower down the order of things (as you would previously have understood it) - much lower down.”

Where have these ideas come from? There are two main routes by which forest gardening came to the (white-dominated) Western alternative food movement. In many cases, it’s part of the ‘permaculture’ package of design techniques which David Holmgren and Bill Mollison took from white ethnographers studying tropical indigenous food forests in the late 70s. The other route comes from Joseph Russel Smith, an American advocate of food forests in the mid-20th century, who inspired Toyohiko Kagawa, a Japanese activist, who inspired the English Robert Hart who is credited for creating the first temperate forest garden and has inspired today’s advocates of forest gardening like Martin Crawford.

It’s not clear to me how much Smith took from Native Americans, but there’s plenty of evidence of indigenous temperate forest gardens. The Coast Salish people in Canada have been practising it for hundreds of years and European nomads propagated and tended perennial food forests on their journeys across the continent. Recognising this past matters.

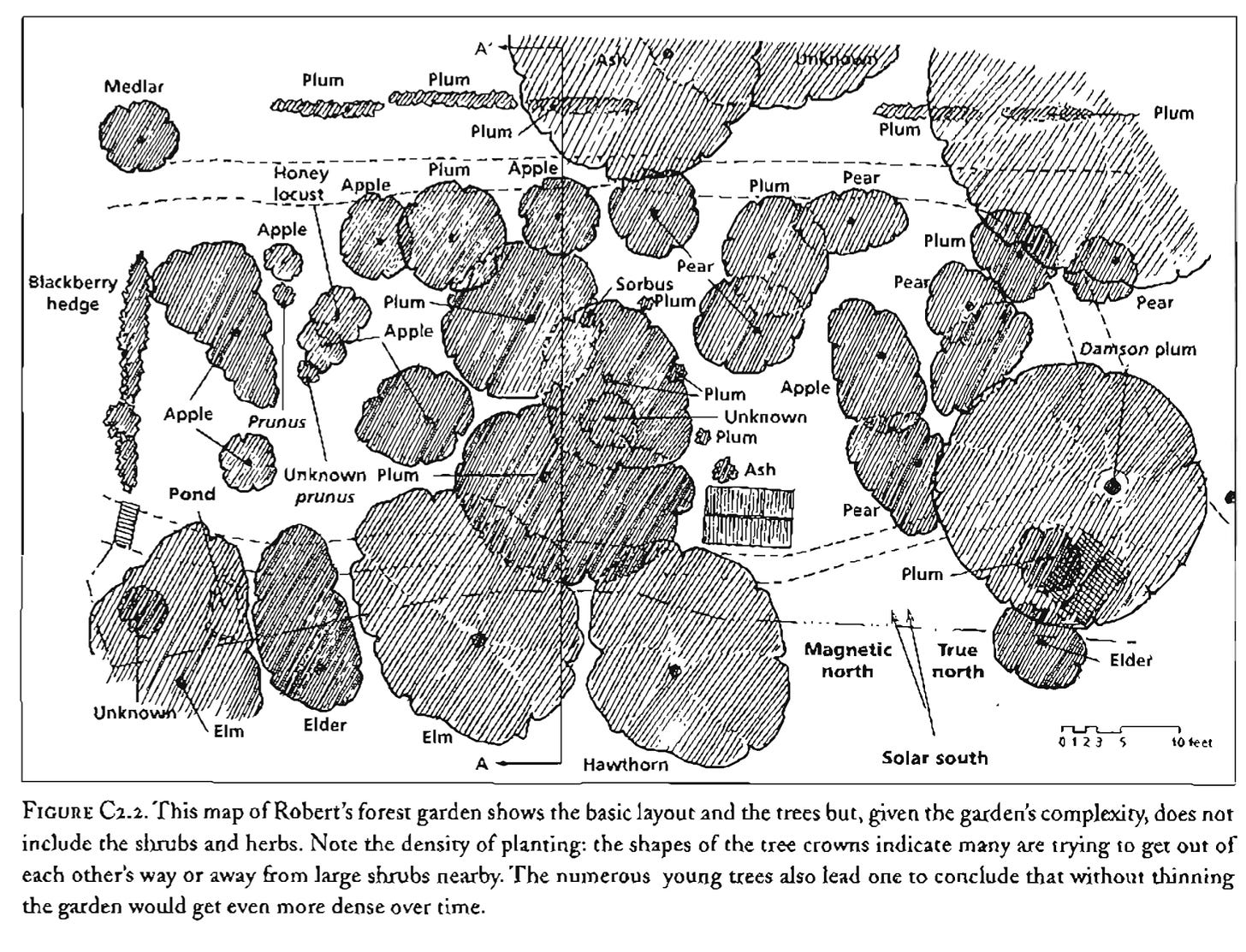

For one, as you can expect from someone with no prior experience of actually existing forest gardening, Robert Hart made many mistakes. He was overzealous with his planting, blocking precious light from his shrub layer. Contrary to what the name implies forest gardens must retain an open canopy to let light through the whole system. The last reports I could find from 2017, show his garden reverting to a woodland, with the shrub layer almost totally gone. Compare this with a recently rediscovered forest garden last managed by the Sts’ailes in Canada 150 years ago which is still producing food and has somehow resisted being overrun by the conifers surrounding it.

For two, the critiques of permaculture - that it amounts to the unacknowledged theft of indigenous land practices - apply to forest gardening too. The problem of plucking agricultural techniques from a wider web of social relations isn’t just a moral one. Although it is a shitty thing to do given the history, it also sets the Western alternative food movement up for failure because we lose the political culture we need to make change last.

Forest Gardening, according to Robert Hart, “has a major role to play in the evolution of an ‘alternative’, holistic world order. A Green World. The world of Gaia.” But what is this role beyond rippling out by chance imitation? What someone said recently about permaculture applies to Western iterations of forest gardening too: “It has no theory of change. While it offers incredibly detailed guidelines for how to make change on one specific piece of land, it has little of use to say about the bigger picture.”

Indigenous people have had to fight hard to keep their land and most are still fighting to reclaim what’s been stolen. Take the Mohawk in Oka in 1990, the Wet’suwet’en neighbours of the Sts’ailes defending their forests today. Or take the Zapatistas, a composite of Indigenous peoples, including the Maya whose ancient forest gardening techniques reveal an alternative civilisational form and dispel the myth of Mayan collapse.

As one member of the Muckleshoot people put it: “At the core of tribal sovereignty is food sovereignty. This is significant because we know that our traditional foods are a pillar of our culture, and that they feed much more than our physical bodies; they feed our spirits. . . . They are living links with our land and our legacy, helping us to remember who we are and where we come from.”

Taking polyculture guilds and dropping the struggle isn’t only a crude disassembly of intricate ways of life but misses the point that forest gardens, no matter how productive, visually appealing, or biodiverse, can’t be safe in a system designed to accumulate capital at all costs.

This is playing out for us live with the threatened eviction of Martin Crawford’s famous forest garden by the Dartington Trust last month. Even the OG forest garden in the UK, with highly reputable supporters in the conservation elite, is vulnerable to the needs of capital to extract value from land. So far 30,000 signatures and a flurry of public outrage have dissuaded the Trust from following through with the eviction. Time will tell whether the counterculture of Totnes has an adequate political culture to protect what it loves.

This is what I think the real power of the forest garden as an idea is: it could help us all along a journey through stages of political consciousness: it pulls us in with the promise to end hunger, or protect nature; then it insists on a much deeper restoration of relationships; then, if we look closely at its routes, it can illuminate paths for collective action and international solidarity.

I've never thought about forest gardening needing a ToC before... I'm not sure everything does, but this has certainly been thought provoking.

I've read Robert Hart's book and fwiw, he does make clear that he didn't invent forest gardening and that many cultures had practiced it in one form or another for a long time.

I love the hopeful ending of this essay anyway, thanks 🙏🏻

You would never catch me being overzealous with my planting and blocking precious light from his shrub layer